Fermín Jiménez Landa

4 / 17

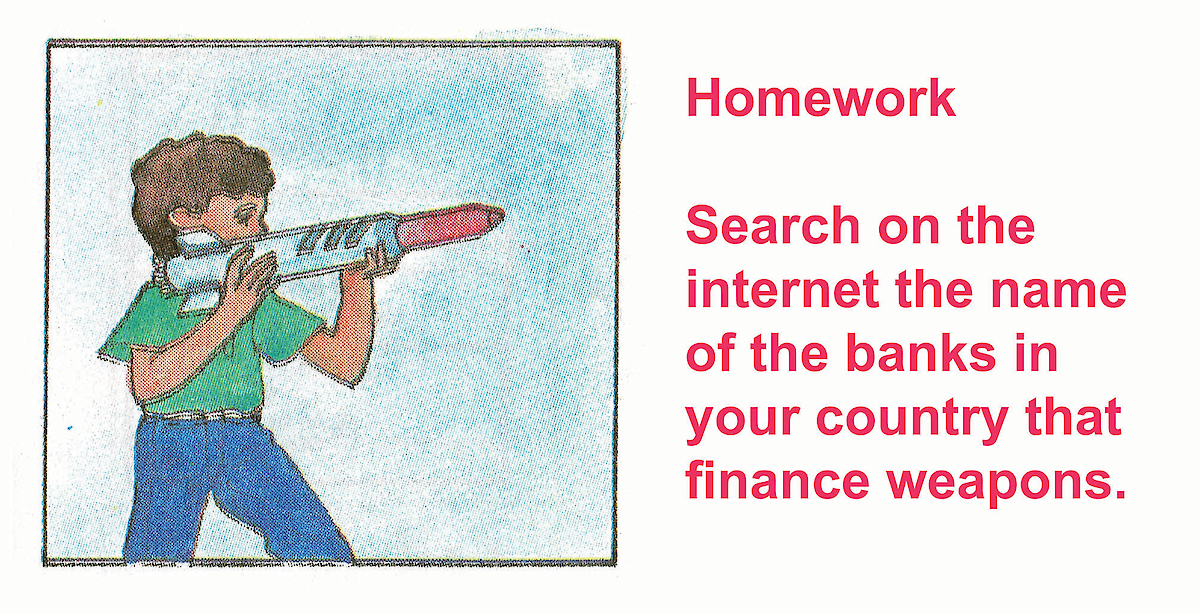

Homework

The type of line in this illustration takes us back to a type of drawing commonly found in school textbooks. As a matter of fact, this illustration comes from a children’s textbook. Its naïve style does not hide the harshness of the image: a child carrying a missile, a weapon.

The type of question that accompanies this image reminds us of the type of language used in classrooms. Questions are classic educational resources whose aim is to make students do research so that they can give the right answer —if there is only one— or to foster a critical reflection on the proposed subject.

Even though neither this type of format (i.e. illustration) nor this type of medium (i.e. a poster displayed in a public space) are commonplace in Fermín Jiménez Landa’s work, the strategy that has led to its embodiment most certainly is: an intervention in reality with a minimal gesture. In this case, it was about presenting a provocation about the way information is transmitted by decontextualizing an already existing image.

Jiménez Landa’s works are based on an initial presupposition embedded within the logics of capitalism, which he follows to the letter, as if it were a child’s game, thus revealing the multiple inconsistencies and failures of the system. In order to reflect on the 2030 Agenda, the artist has focused on the use of language and images made by most international agencies in their communications, such as the one in this campaign, as well as on the type of physical presentation used in this project, i.e. a large poster at the entrance of a building. When taken to extremes, as in this case, the use of the typical forms of advertising through direct communication that seeks to create an impact as a strategy can push the envelope of what can or cannot be said.

Homework raises an uncomfortable question, which, if the viewer cares to investigate, will have a very specific answer. But Fermín does not give it to us. As he reminds us, “Art, as they say raises questions; it does not provide answers, although it may make us uncomfortable.” Thus, his works do not involve direct activism, but give us, as spectators, the opportunity to assume the responsibility of searching; in other words, the ability to develop critical thinking, not just a repetition of data.

Likewise, without giving any hard facts to solve the problem posed, the image and the text make us reflect on other issues surrounding the purpose of SDG 4. Even though UN indicators show that the rate of children enrolled in primary school has now reached 91%, more than half of the out-of-school children live in sub-Saharan Africa and/or in conflict-affected areas.

Within the proposals of this goal, point 4.7 states: “By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.”

The book from which Fermín has extracted the image was neither published nor distributed in the so-called “First World” countries.