Claudia Claremi

15 / 17

The memory of fruits

It should not be difficult to reach a consensus and determine what we are talking about and who we are referring to when a title refers to “life on earth.” Life as existence, existence as reality. The reality referred to in the 2030 Agenda’s objectives determines a distinction between types of lives.

Division still remains when addressing the concept of nature as something alien to man, and therefore to civilization, the same one that has driven development and anthropocentric thinking: “To meet Goal 15, a fundamental change in humanity’s relationship with nature is essential, along with swift action to address the root causes of these interconnected crises and for a better recognition of the enormous value of nature.” If this is the basis of the reasoning, any measure will always be biased and determined by an exclusionary and utilitarian starting point, as can be read in statements such as “terrestrial ecosystems are vital for sustaining human life” or “promoting the fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and promoting adequate access to these resources, as internationally agreed.”

Humanity is nature, humanity is an equal part of any ecosystem on Earth, not only terrestrial. But, in addition, due to the predatory action for reasons not of survival but of hegemony (or plundering, colonization, extractivism), the human species has the responsibility for the sustainability of life on the planet being viable, even regardles of its own sustainability as a collective.

The root problem of this determination is the dividing and absolutist classifying capacity that it can lead to. Which species, which races, which living spaces are the priorities? Difficult question to answer when we share realities between species, such as migration for economic reasons. It is in the field of reality that the artist Claudia Claremi works.

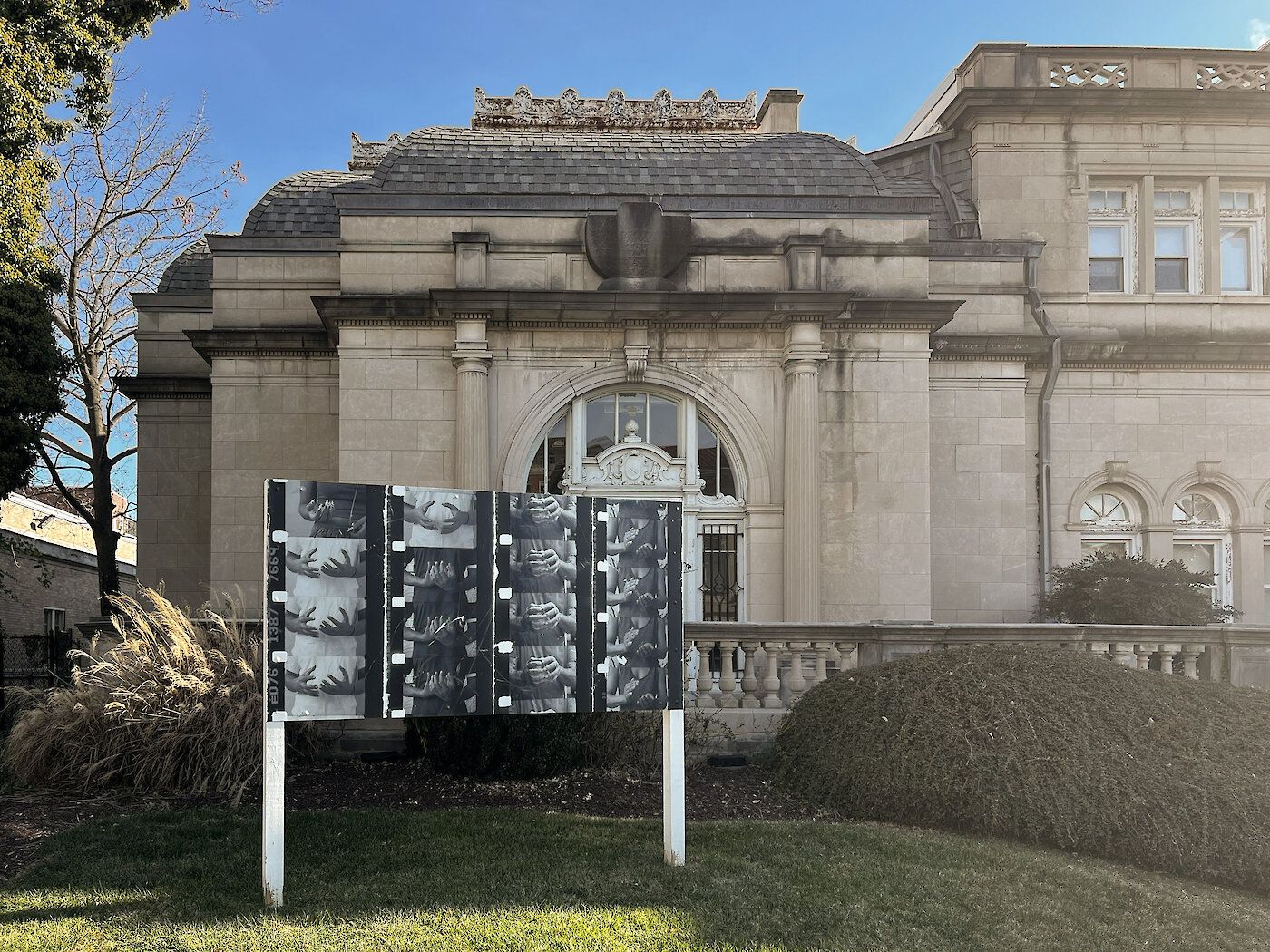

Tracing economic transits of people —the Caribbean diasporas— and mercantile ones —the massive, extensive and timeless production of certain species of fruits in the face of the disappearance of others— Claremi investigates the affective memory of the crossing of both species. The The memory of fruits project, which is installed within this critical program at the entrance of the Cultural Office of the Spanish Embassy in Washington, D.C. to activate a review of SDG #15, rescues the relationship of sensory memory: They are people who, far from their homeland, evoke the fruits that they can no longer find in the new contexts in which they live.

It is a gestural, visual and oral registry that, recorded in text or images, (16mm film developed by hand) evokes shapes, smells, tastes and textures, but also a space and moment that refers to a collective experience. A reflection that, as the artist describes, speaks of situations that concern “each context of origin or, in the global market, affect both fruits and people.”

With this poetically stated certainty about equality, meditation leads us to reread objectives such as “Take urgent action to end poaching and trafficking of protected species of flora and fauna, and address both demand and supply of illegal wildlife products” or “introduce measures to prevent the introduction and significantly reduce the impact of invasive alien species on land and water ecosystems, and control or eradicate the priority species.”