Nicolás Combarro

5 / 5

Background, 2023

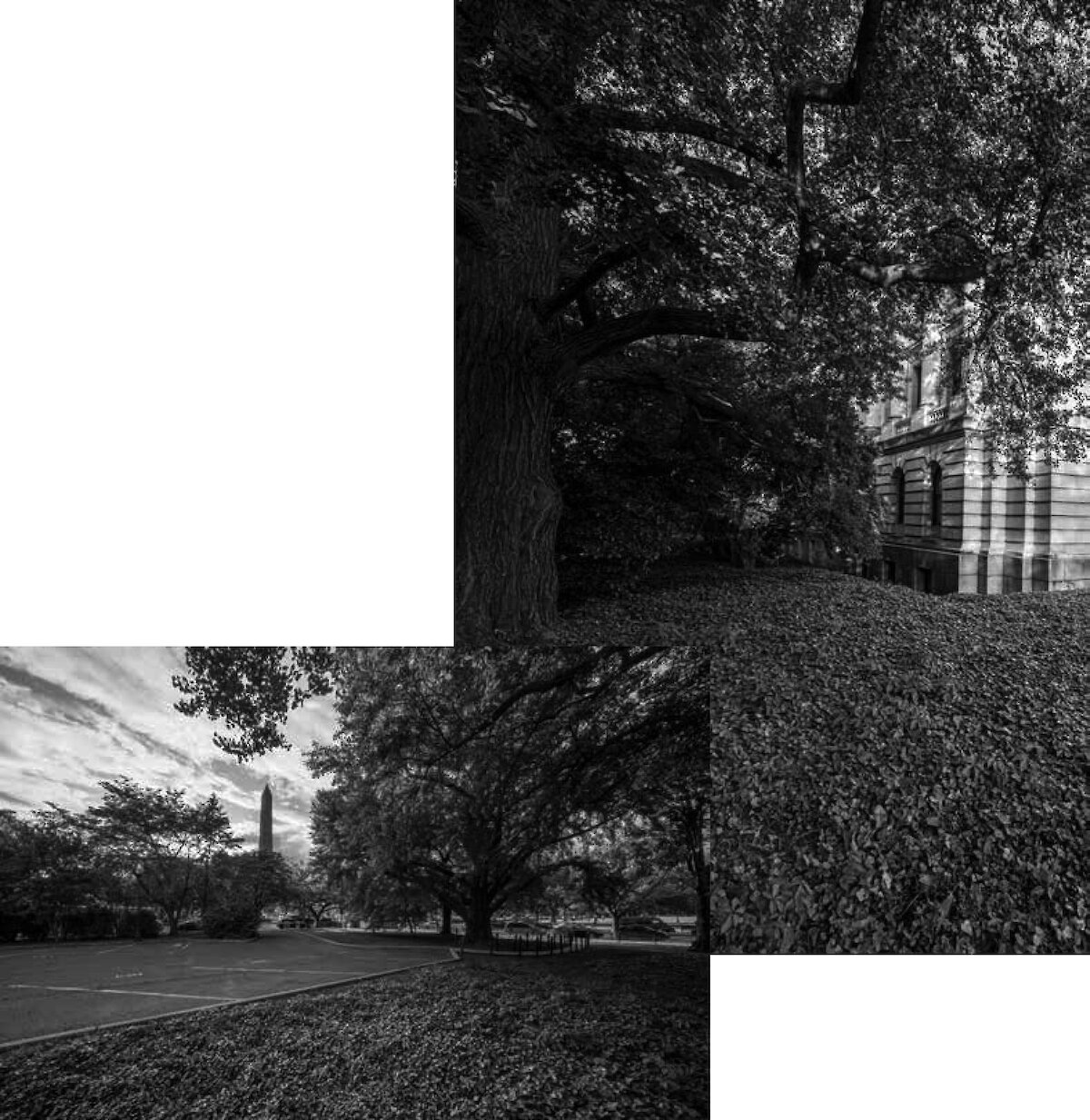

Washington, D.C. is a young capital that was founded in 1790 as a symbol for the equally new country. Its identity was largely constructed via major government buildings such as the White House and the Capitol, but also via various memorials and monuments.

Many of these icons depict historical figures or achievements that form part of the collective memory, but other monuments go unnoticed or are barely known. In both cases, this lack of attention can be due to ignorance on our part about the history surrounding them, difficulties associated with their construction, or the weight of the past borne by the figures represented therein. Some aspects have been hidden from view, while the sociopolitical contexts in which these monuments were created made it possible to celebrate viewpoints that are now extremely problematic.

Monuments have always given rise to controversy, and in our times there are various movements in many countries demanding that they be interrogated, recontextualized, and, in some cases, removed altogether (for example, the Monument Lab in the USA and Uncomfortable Monuments in Chile). In Spain, we have spent decades trying to approach our own memory from the standpoint of historical reparation, involving a review of the Franco-era monuments that still spark controversy, but there has been a reluctance to confront other ineluctable historical topics such as colonialism, which other neighboring countries are indeed grappling with.

This project delves into this background, as the stories around these monuments and the controversies they arouse today prompt us to study their contexts more closely and observe them with a critical, historical, and political gaze.

Eighteen steps away from the Lincoln Memorial, an inscription marks the spot where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I have a dream” speech in 1963. The carved stone was laid in 2003 to commemorate the 40th anniversary of that speech, in which he evoked the emancipation of the slaves and the “shameful condition” of segregation still prevailing in the United States one hundred years after the Civil War. The speech was the climax of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which was a decisive moment for the civil rights movement as it helped apply pressure on lawmakers to pass the civil rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965.

When this memorial was unveiled in 1982, its design by Maya Lin (the winner of a public competition for the commission) sparked various controversies due to its minimalist style, its placement below ground level, and the blackness of its granite, amongst other objections. Lin herself, the child of Chinese migrants, was even subjected to racist and misogynist attacks. Two years later, in an attempt to dampen the controversy, a more “traditional” monument depicting three armed soldiers was built opposite Lin’s memorial, after a design by the sculptor Frederick Hart. Maya Lin received $20,000 for her design —while Hart charged a fee of $330,000 for his.

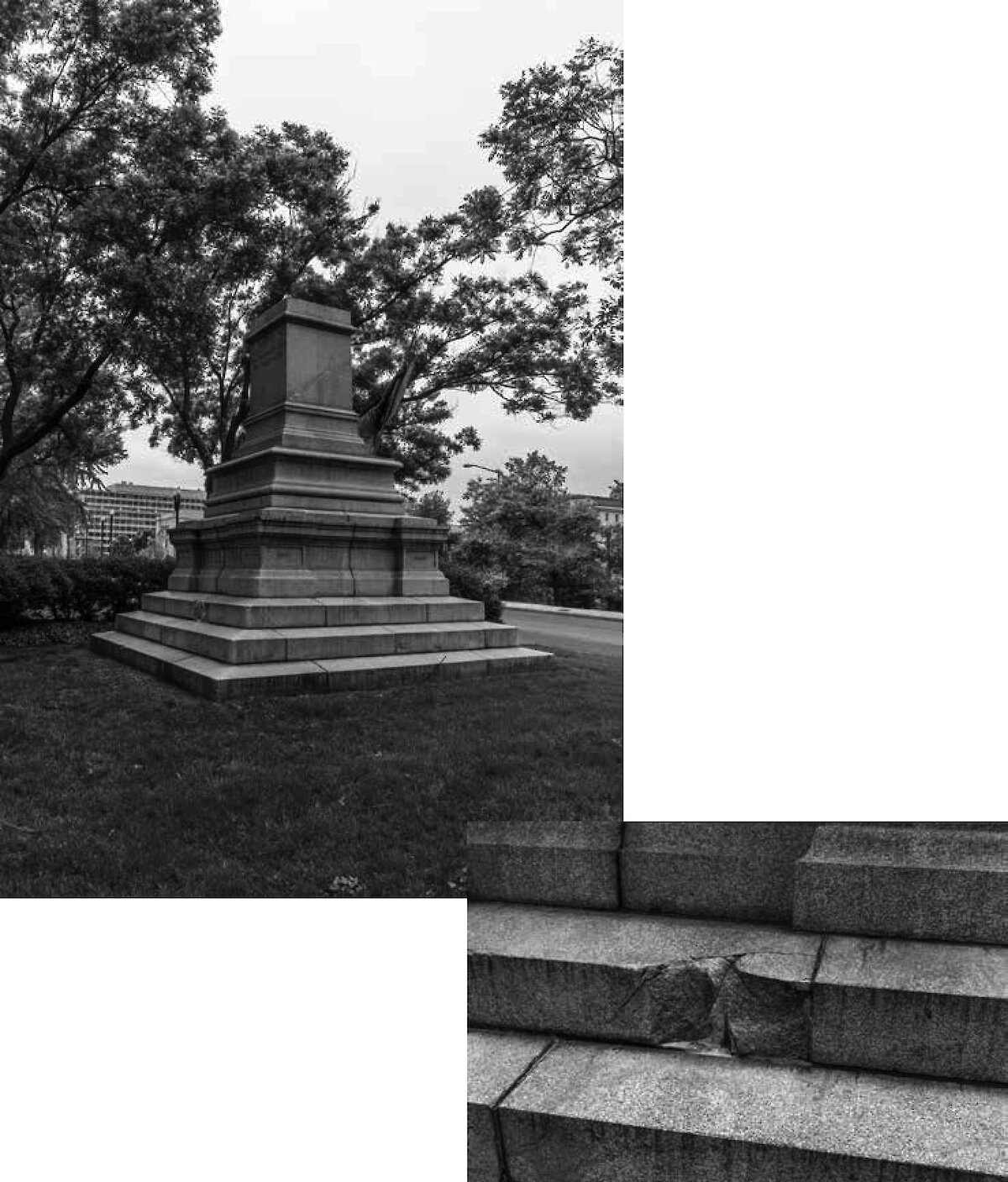

Pike was a Confederate General who was accused of treason by both sides in the American Civil War. He defended slavery and was a member of the xenophobic Know-Nothing American Party and, allegedly, the Klu Klux Klan. His statue was unveiled in 1901, on the same spot where the pedestal now stands, but the approval for its construction had already sparked opposition from the GAR, an association of Unionist veterans. There have been various campaigns for its demolition since 1991, including petitions to the US Congress in 2017 and 2019. In June 2020, the sculpture was knocked down and its pedestal was daubed with graffiti by activists from the Black Lives Matter protests.

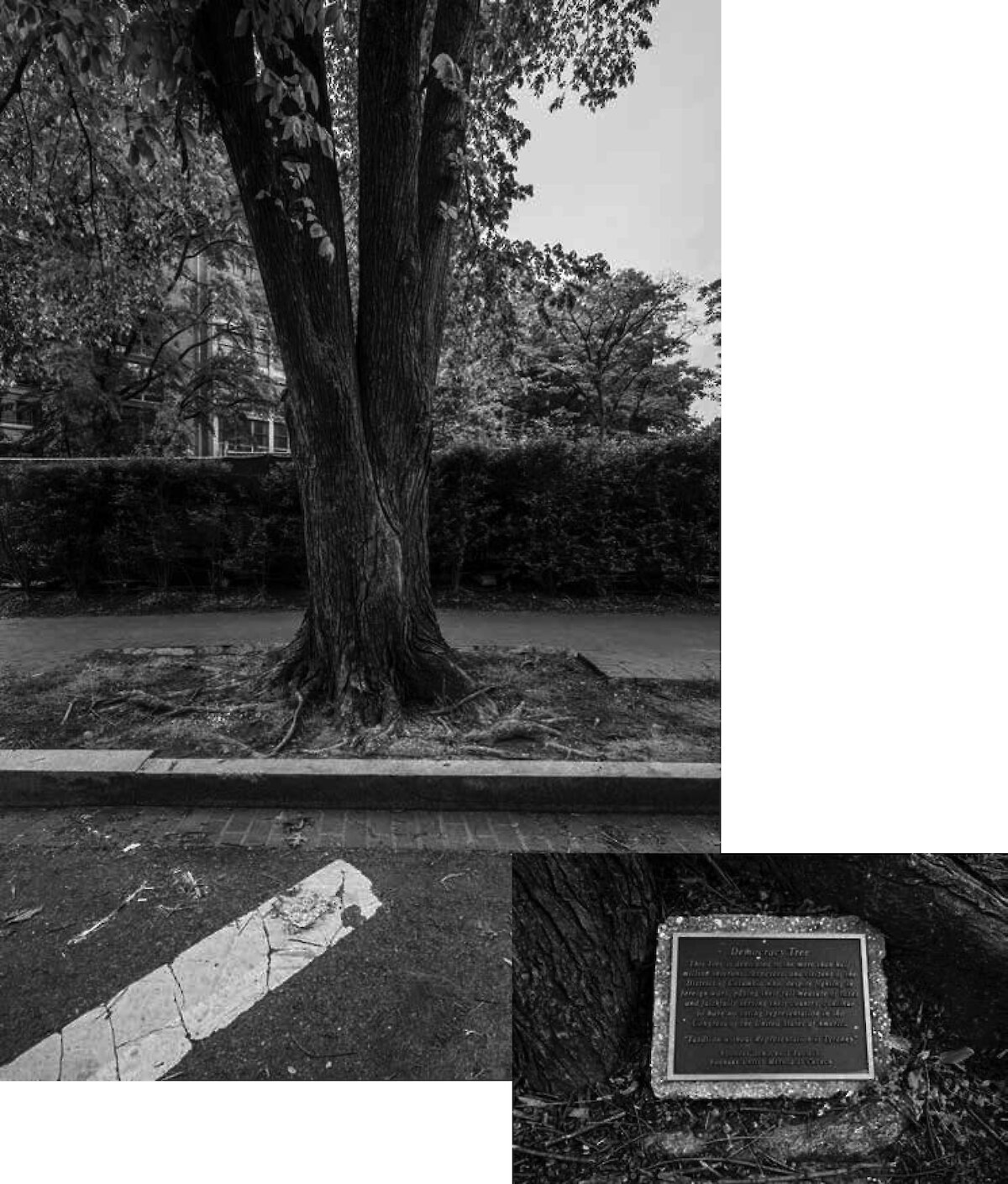

The plaque at the base of the tree bears the following text: “This tree is dedicated to the more than half million veterans, taxes, and citizens of the District of Columbia who, despite fighting in foreign wars, paying their full measures of taxes and faithfully serving their country, continue to have no voting representation in the Congress of the United States of America. Taxation without Representation is Tyranny.” The plaque was installed by the Foundry Democracy Project, which seeks to educate the federal government and the general public about the need to provide the people of the District of Columbia with the right to vote in Congress.

In June 2020, the Speaker of the US House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, called for the removal from the Capitol of eleven statues of Confederate officials who opposed the abolition of slavery. Some of these statues have been placed elsewhere, but the majority remain exactly where they were —including that of Alexander Stephens, the vice-president of the Confederate states responsible for declarations such as: “Our new Government is founded upon exactly the opposite ideas; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.” As Pelosi explained: “While I believe it is imperative that we never forget our history lest we repeat it, I also believe that there is no room for celebrating the violent bigotry of the men of the Confederacy in the hallowed halls of the United States Capitol or places of honor across the country.” Pelosi’s proposal was supported by Representative Zoe Lofgren, a member of the House Committee responsible for the National Statuary Hall Collection: “The Capitol building belongs to the American people and cannot serve as a place of honor for the hate and racism that tears at the fabric of our nation, the very poison that these statues embody.”

On September 26, 2014, President Barack Obama signed legislation granting permission to put up a National Liberty Memorial on the National Mall, alongside the Department of Agriculture Building. This commemorative monument would pay homage to the 5,000–10,000 enslaved and free individuals of African descent who provided assistance to the cause of Independence by enlisting as volunteer soldiers and sailors in the American Revolutionary War. Tens of thousands of slaves fled toward liberty, and men, women, and children demanded their freedom in State courts and legislatures. At the time of writing, the monument has not yet been erected and its location is still under discussion.

Quotation from Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton (D-DC), February 24, 2021: “My bill to remove this statue of an unabashed racist from Lafayette Park will be introduced next week. Lafayette Park itself has a painful past as a slave market. The statue of Andrew Jackson, who himself enslaved African Americans, compounds this insult. This prominent location in the nation’s capital, right outside of the White House, should never have honored a man who owned slaves and was responsible for the deaths of roughly 4,000 Native Americans. Jackson’s entire tenure is a shameful part of our history. […] I believe that this statue should be preserved and placed in a museum, not displayed prominently in the nation’s capital. The next generation can learn from this painful chapter in our history without celebrating it.”

Public artwork located in Meridian Hill Park, known informally as Malcolm X Park. In 1916, Charles Deering commissioned the Catalan sculptor Josep Clarà i Ayats to create a depiction of “serenity” for the main patio of his villa in Sitges. However, subsequent alterations to the building forced Deering to change his plans, and he ended up placing the statue in Meridian Hill Park in honor of his friend and former classmate in the US Naval Academy, William Henry Schuetze (1853–1902). When the statue was eventually installed in 1925, a petition was launched against it on the grounds that certain “things” were “too big,” in reference to the sculptural proportions of the figure’s breasts. Members of the local community attacked the sculpture with hammers, causing damage that is still visible today on the woman’s face. In 1960, the statue was reported to be missing its nose. In 1993 it was officially inspected and declared to be in need of restoration. In 2009, press reports announced that it also lacked its left hand and a big toe. In 2018, one of the sculpture’s hands was also missing.

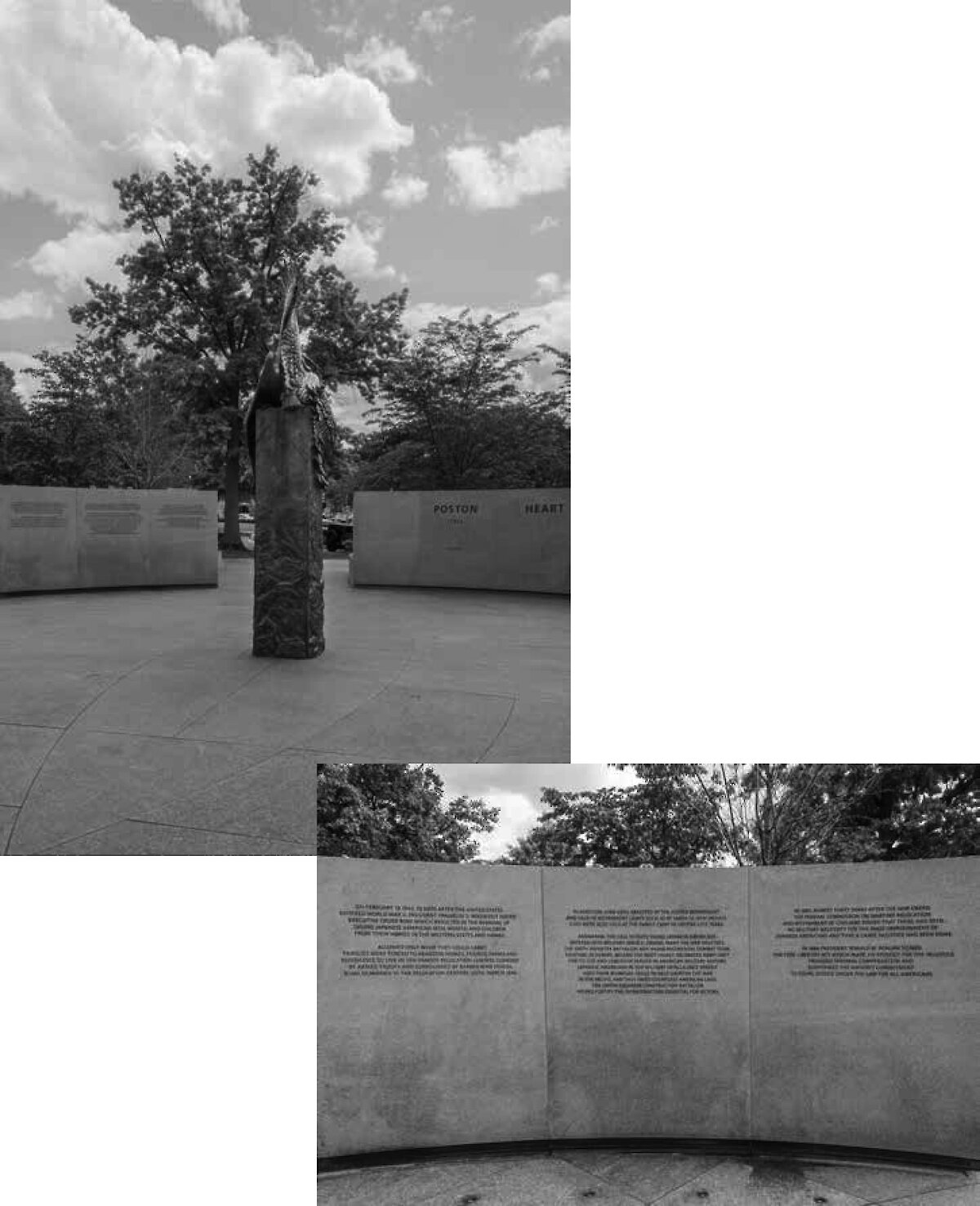

Quotation taken from the inscriptions on the monument: “On February 19, 1942, 73 days after the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which resulted in the removal of 120,000 Japanese-American men, women and children from their homes in the western states and Hawaii. Allowed only what they could carry, families were forced to abandon homes, friends, farms and businesses to live in ten remote relocation centers guarded by armed troops and surrounded by barbed wire fences. Some remained in the relocation centers until March 1946. In addition, 4,500 were arrested by the Justice Department and held in internment camps, such as Santa Fe, New Mexico. 2,500 were also held at the family camp in Crystal City, Texas.”

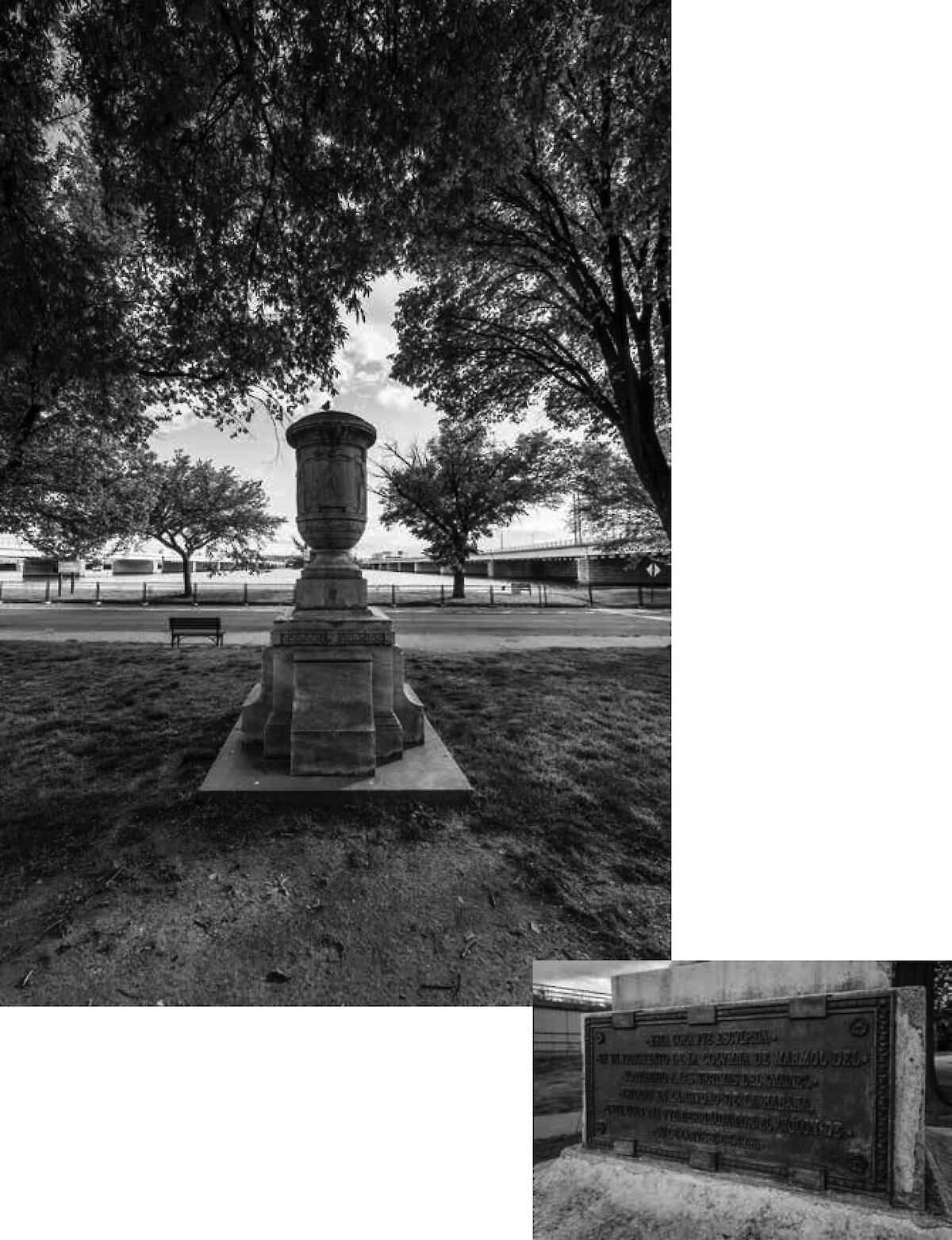

Transcription of one of its plaques: “This urn was sculpted from a fragment of the marble column of the Monument to the Victims of the Maine. Erected in the City of Havana, this column was taken down by the hurricane of October 20, 1926.” Gerardo Machado, the President of the Republic of Cuba, donated this monument to the American President in 1928, and it was put in East Potomac Park (close to its current placement). After the relationship between the two countries deteriorated when Fidel Castro came to power in 1959, the urn reportedly stood for many years in front of the Cuban Embassy on 16th Street, NW. The official version maintained, however, that the urn had been removed due to the construction of a bridge on 14th Street and was then forgotten. In 1996, an article in a local newspaper was accompanied by a photograph of the urn lying in a warehouse belonging to the Park Service. This revelation triggered the rehabilitation of the monument, and it was returned to East Potomac Park in 1998.

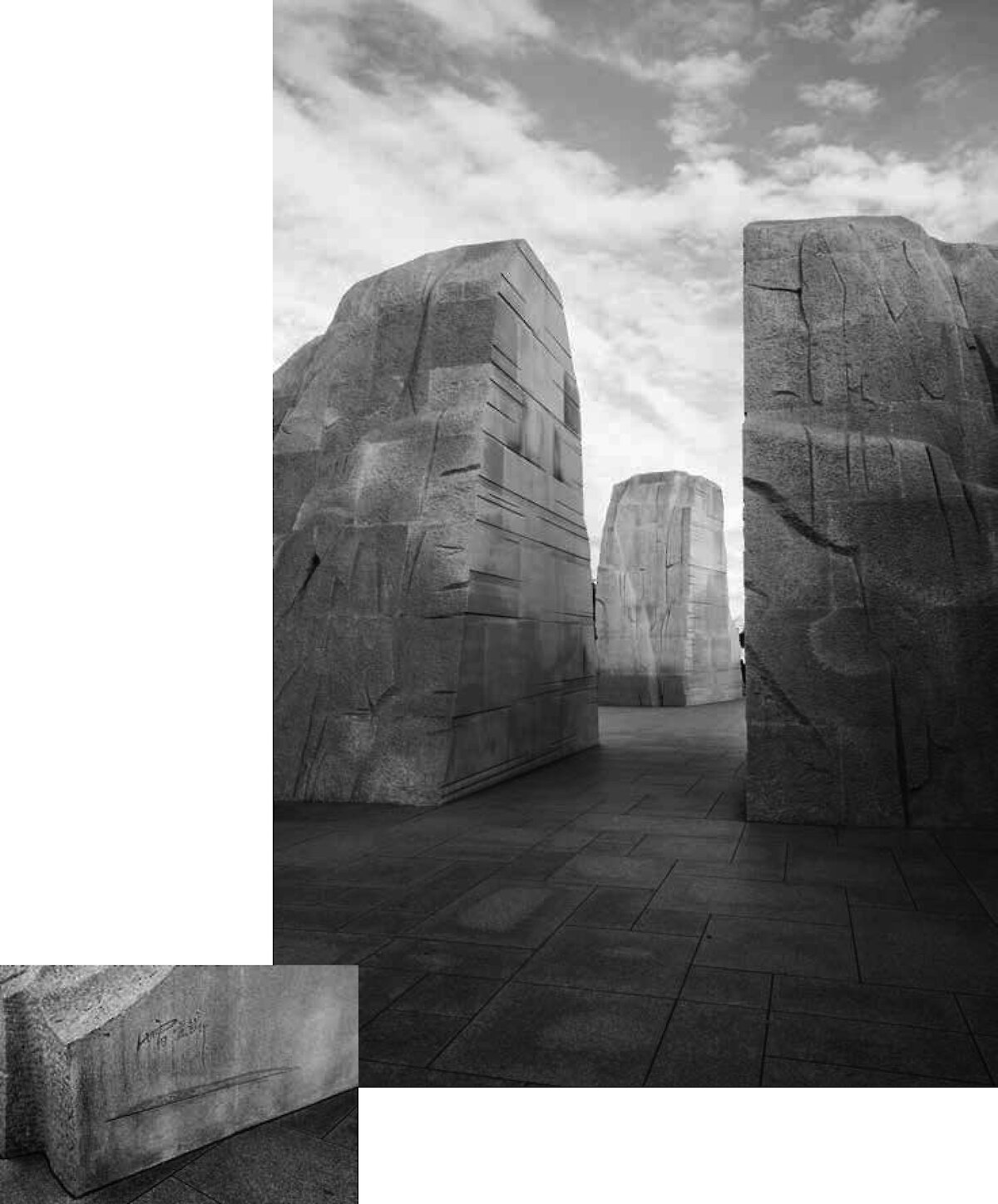

The first memorial to an African American historical figure on the National Mall. Unveiled in 2011. This monument was surrounded by various controversies right from the start: the Chinese sculptor who received the commission, Lei Yixin, was apparently obliged to work in collaboration with the African American Ed Dwight (who had been commissioned to produce the memorial’s original design) and the two did not see eye to eye. The choice of stone —“white” granite shipped in from China— was also criticized. There were reports that the workers on the sculpture (who were also brought in from China) were not unionized and had irregular contracts. Furthermore, one of the quotations inscribed on the memorial contained a paraphrase of Dr. King’s actual words and subsequently had to be amended.