The Institute for Postnatural Studies

6 / 17

Polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride

Although the economic and social theories of the last decades remind us that in the digital era “everything solid vanishes into thin air” —now that currencies or gold are no longer the standards that govern digital operations in the cloud, and despite the fact that relationships become liquid and disembodied— there is one hard fact that we can be sure of: There are 14 million metric tons of plastic on the ocean floor.

The term “microplastics” is used to describe a multitude of particles less than five millimeters in size, while the term “nanoplastics” is used for particles no larger than one micron. All of them, with their own characteristics —chemical composition, density, shape, etc.— pollute the world’s rivers and seas when they reach the water in the form of waste, whether due to atmospheric precipitation, wastewater, overflows, industrial effluents or the degraded remains of plastic items in the garbage, such as plastic bottles and caps that people forget to put in the recycle bin. All these polymers pose a risk to the health of all living creatures, not only those who drink water, but also the ones that are in contact with it, either as particles, or due to the direct proximity to toxic agents or their accumulation.

The UN reminds us in its goal #6 of the 2030 Agenda that “one in three people do not have access to safe drinking water,” so it proposes to “achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all” and “improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally.”

The question raised by the research and education platform of the Institute for Postnatural Studies places particular emphasis on the layers involved in talking about equal access to drinking water, considering that, as the National Geographic stated in one of its issues, “we swallow up to 50,000 plastic particles each year,” or as the TappWater company claimed in its advertising campaign for water filters: “You are drinking a credit card of plastic every 2 weeks.”

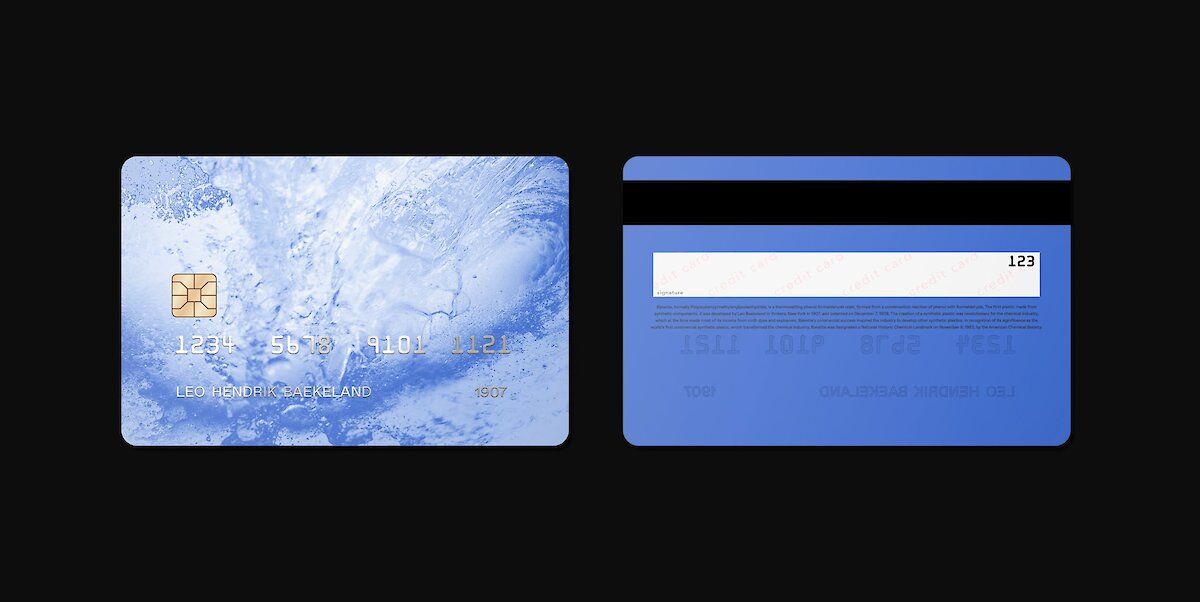

With these images as inspiration, the design that the IPS has created for the project Not only the what, but also the how refers directly to the concept of plastic money: the rectangular cards that provide credit for everyday transactions in the most developed economies. The holder of this card, Leo Hendrik Baekeland, was the inventor of Bakelite, the first industrial synthetic resin in 1909. As a result, his card, decorated with the blue color of water, becomes the trigger for several questions: Who will have access to a resource that is seen as scarce, and consequently, has an economic value or to the technology for filtering this invisible toxicity? What is the role of large investment funds and the policies adopted to protect their interests around privileged and controlled water resources? And how do these illicit chemicals affect all those other lives deprived of an agency in this system? In short, it is about keeping in mind the fundamental and inextricable economic and material dimension that comes with the expectation of promising clean water for “everyone.”